Should we tip machines for the work they do for us?

Does that question even make sense?

What follows is a reflection on metaphors, technology, deceptive design, AI and more… Read on.

Metaphors and more

In her book God, Human, Animal, Machine, Meghan O’Gieblyn discusses how we use metaphors when talking about technology. She argues that metaphors are powerful framing devices that shape how we think about the world. When we use technological metaphors to describe human traits (like calling the brain a “computer”), it reflects and reinforces the view that humans are machine-like. This can lead us to think about ourselves in reductive, mechanical terms rather than as complex, spiritual, emotional beings.

On the flip side, when we anthropomorphize technology by ascribing human qualities to it (like saying an algorithm “thinks” or “decides”), it colors our perception of that technology. We start to treat it as human-like and assume it has capacities it doesn’t really have. O’Gieblyn argues this is happening more and more as AI systems become advanced.

O’Gieblyn’s core point is that metaphors create associations in our minds, and bidirectional metaphors between humans, animals, machines, and the divine shape our conceptual frameworks around these realms.

These are indeed thought-provoking ideas – what I was not expecting that these metaphors would become real.

(Incidentally, Nicole Oster and I recently coauthored a review of God, Human, Animal Machine and The Alignment Problem for the the Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning. The article is worth reading, if I say so myself, for the abstract alone, which was entirely written, in first person, by Claude.AI).

The Tipping Point

Coming back the story…. Let us consider the idea of tipping—a somewhat odd custom where we voluntarily pay extra money directly to servers, drivers, and hair stylists because their bosses don’t pay them enough!

Tipping, back in the day, used to be relatively straightforward. You would calculate by yourself, what the service, say being served a meal at a restaurant meant to you, and you would leave cash on the table. Not any more. Subtle techniques of coercion have been built into service systems to encourage us to tip. Now tip suggestions and percentages are baked right into our payment terminals and apps. Restaurant bills, taxi screens, and takeout order portals all display pre-calculated tips of 15%, 20%, or even 25%. These systems do two things, move tipping from being voluntary to being the norm and as importantly anchoring certain percentages in our minds thus nudging us to tip more generously. These are subtle pressures, but effective none the less. I haven’t studied these systems closely, but I am sure that the higher amounts are put there so that people will go for the amount in the middle – rather than go for the extremes, one appears stingy and the other excessive. This is smart (if somewhat dubious) psychology.

To be honest, apart from the rising percentage these systems haven’t really bothered me too much, since it has made the process of tipping somewhat easy, and saves me time since I don’t have to calculate the exact amount (typically 20%).

All that said, one technological innovation I was NOT expecting was that I would be asked to tip a self-service check-out machine. Quite definitely not on my bingo card for 2024!

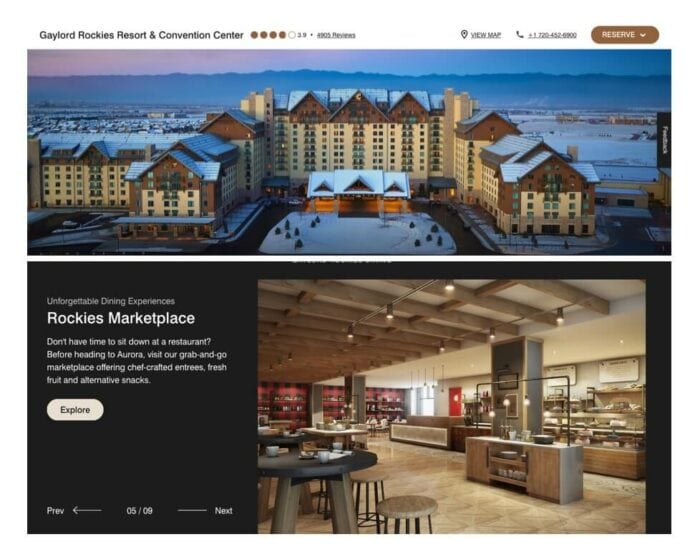

This, however, was exactly what happened the other day when I was at the annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education held at the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center in Denver. Specifically at their “grab n go” Rockies Marketplace.

This was first brought to my attention by my friend Marie Heath when she was asked to tip a self-serve Checkout machine, while purchasing a snack. I, of course, HAD to go back the next day and buy something just to get the photo below.

Note the “Self Checkout” sign at the top left and the options to select a tip on the right. Also important to mention is that the system will not allow you to continue the transaction without making a decision on tipping. This is not obvious in the photo but the progress bar on the left screen essentially freezes and will not let you go to the next step until you have taken a decision on tipping.

Bad design v.s. Deceptive Design

Encountering this of course brought up a whole bunch of interesting questions for us to ponder. Would the machine feel obligated to return the amount tipped, since we had done all the work, of finding what we needed, carrying it over to the checkout machine, scanning it in and paying for it? Would it preform better the next time I came by if I had tipped it more? If tipping people means that they are not paid enough, does this mean that these machines are not being paid well? Would it be sad if we hit the “No Tip” button?

But jokes apart, we also wondered about how many people, just out of habit, hit the 18% or 20% button?

To me this a great example of deceptive design—which is a step beyond bad design. Bad design lies in the fact that it adds an extra (non-essential) step to the check-out process. Deceptive in that it attempts to trick us into spending more.

It also got me to thinking about Meghan O’Gieblyn’s idea that metaphors work in mysterious ways, often blurring the lines between the tangible and the abstract, the playful and the profound. What started as a physical act (literally the tip jar) now becomes an abstract process that has a life of its own. It shows how deeply ingrained metaphors can shape, and sometimes distort, our interactions with the world (and can be used to manipulate us).

Tipping Generative AI

These metaphors can come to life in some other stranger ways as well. For instance I have written about the weird fact that there is some evidence to show that one can improve ChatGPT’s performance by offering it a “tip.” Tipping a large language model seems strange – maybe even stranger than tipping a self-service machine. At least in the case of the physical machine, we know that was designed by humans, and designed to deceive. But in the case of large language models, it is a behavior that emerges from the strange mysterious computations that these large language models do based on being trained on human data.

We do live in a strange, strange world.

Fascinating – I am definitely that person who will instinctively tip but its not entirely because I am mindlessly doing it. My best friend ran a restaurant for 15 years, is a well known vegan chef nationally and after 20 years of observing her, it became instinctive to me to always tip well. Even in the case of the above machine, my hope is that those tips will be distributed to those that are working to restock or maintain the space, I don’t think my mind ever went to the notion that I am tipping a machine until I read this which definitely is an interesting thought!