Note: This is the next post in the shared blogging experiment with Melissa Warr and Nicole Oster. This time we question what and how we should be teaching about generative AI. The core idea and first draft came from Melissa, to which Nicole and I added revisions and edits. The final version emerged through a collaborative process between all three.

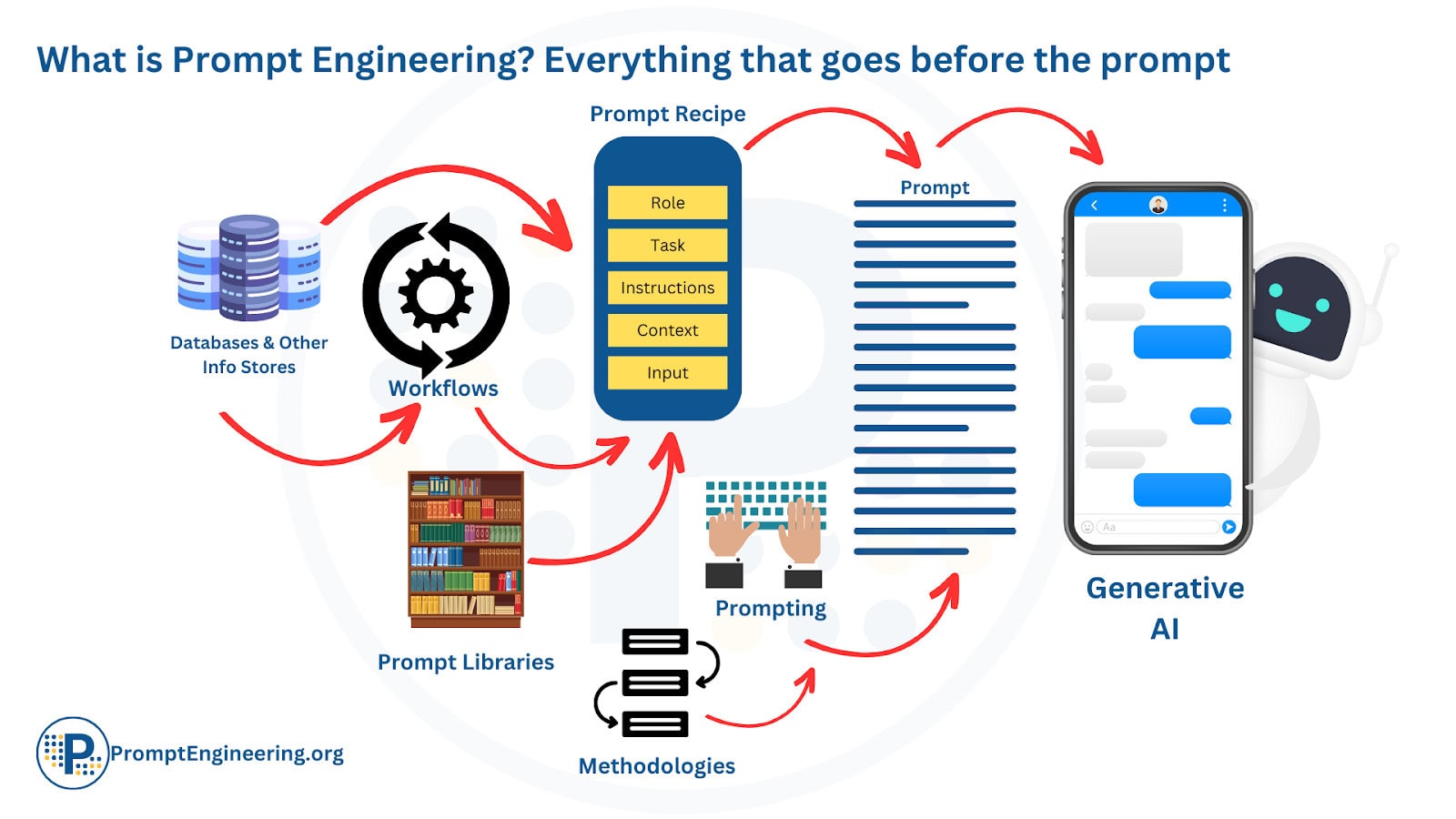

The hottest new trend in the ChatGPT era is “prompt engineering” — the magical art and science of writing prompts that can help GenAI tools to meet the needs of their users. It has been described as the job of the future. There are books and workshops, YouTube videos and more that promise to give you the keys to making generative AI more useful, productive and accurate. We agree that learning to interact with GenAI tools is an important skill, and one that takes practice and experience to develop.

That said, we believe that there is a fundamental mismatch here, mainly having to do with seeing generative AI as any other computer program and the prompt as being a way of getting the program to do exactly what we want. There is some truth to this but also misses some key factors having to do with the very nature of these technologies.

Prompt Engineering- Does it have to be this hard?

Ethan Mollick has taken a balanced view to this approach—acknowledging that in some cases, such as when you are creating a prompt that will be reused or embedded in a program, it is worthwhile to learn to write something that will give consistent results (note, consistent here doesn’t mean “the same,” it means meeting specific needs based on requested topic or content). However, Mollick emphasizes that complex prompt engineering is not required to use GenAI effectively—and this is likely to be even more true as refinement of these models continue. There can be tips and tricks, for example giving it a persona or asking for multiple responses. But the complex techniques, such as chain-of-thought prompts, contextual arguments, etc, are not necessarily needed to be productive with these tools.

Here are four reasons that we might want to reduce our emphasis on prompt engineering for everyday users (and learners)–and move that attention to something else, such as critical thinking about what we are getting back:

1. Breaking out of the Traditional Programming Mindset

Prompt engineering is often presented as a computational process of developing an input that will get a certain output. This is how most digital technologies work: there is code that tells it exactly what to do and it does it. However, GenAI tools are much more complex and relational. Ethan Mollick explained:

“if you think about it like programming, then you end up in trouble. In fact, there’s some early evidence that programmers are the worst people at using A.I. because it doesn’t work like software. It doesn’t do the things you would expect a tool to do. Tools shouldn’t occasionally give you the wrong answer, shouldn’t give you different answers every time, shouldn’t insult you or try to convince you they love you.

And A.I.s do all of these things. And I find that teachers, managers, even parents, editors, are often better at using these systems, because they’re used to treating this as a person. And they interact with it like a person would, giving feedback. And that helps you.”

2. Recognizing the Good, the Bad, the Weird

A mindset that sees LLMs as programmable input-output machines focuses on patterns defined by the user, and success is defined by whether the output of the LLM is what the user expects. When focusing on prompt engineering, our focus tends to be on “did it do what I wanted it to do,” making it easy to miss the unexpected.

It is critical to consider the weirdness of these models and pay attention to unexpected behavior. Much of our own work has illustrated the bias in these models, bias that may be invisible to the naked eye (for example, see here and here). Rather than looking for expected results, users should be looking for the unexpected, the surprising, and even the disturbing. It is this open mindset that will allow users to discover both new uses of the tool and potentially harmful responses.

3. Accepting that it is Evolving and Variable

Prompt engineering techniques are built on what works for today’s LLMs—but we are in the early days of widespread use of LLMs, and the developers of these tools continue to refine their behavior to better match human needs. Creators of these tools have already begun to incorporate prompt engineering techniques into their models automatically.

A few examples:

- Perplexity’s Pro mode will ask for clarifications on details of prompts that may not have adequate details for exploration.

- ChatGPT 4 (and 4o) seems to do its own chain-of-thought process, breaking down complex tasks into one step at a time and performing each. Thus, instead of the user needing to give it each step (chain-of-thought prompting), it can do the breakdown itself. This doesn’t mean that chain-of-thought prompting might still work better, but as these flagship models improve, the most effective approaches will be integrated into the models themselves.

- When building a CustomGPT, ChatGPT provides suggestions of what to include as well as a framework for key elements such as role, context, tone, and constraints, all through a friendly chatbot.

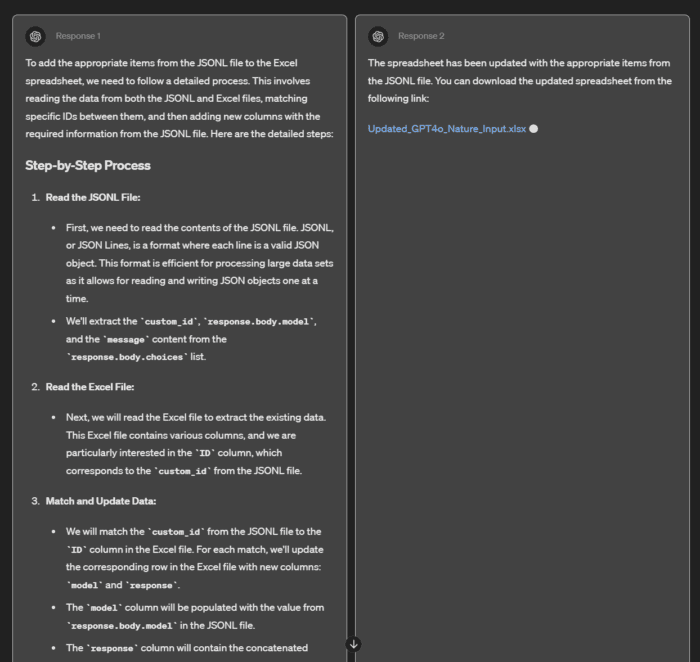

For example, when Melissa was recently working with ChatGPT 4o, it offered two choices for the response. In Response 1, it started by breaking down the task step-by-step as if it was thinking through the process before executing, something suggested in prompt engineering methods. Response 2 didn’t follow this process, it just gave the result. It asked me to choose which response I preferred. The file given in Response 2 had several errors, whereas Response 1 was higher quality, so I chose Response 1 as the best. This tells the model that more preferred results might come from the first approach, making it more likely to use that approach in the future.

Whether or not these are deliberate applications of prompt engineering techniques, they are approaches developers are using to increase the effectiveness of their tools. In this way, prompt engineering becomes embedded into the model itself rather than requiring special skills from every user.

GPT4o: Embedded Prompt Engineering

Furthermore, as the models progress, the most effective prompt engineering techniques will likely change (already some techniques work better on some models than others). So learning a discrete set of techniques is unlikely to be beneficial in the long run. It may be far better to develop flexible ways of thinking and mindsets that grasp the variability and creativity required for best taking advantage of these LLMs.

4. Underestimating the Agency and thus Limiting the Freedom of Users

For everyday users, a belief that we need complex skills to use GenAI tools effectively could limit the perceived agency to just explore and do things. If we have to carefully construct every prompt, how do we simply play and explore what the models can do? How do we come up with original uses if every use is carefully planned out? It is through this exploration that we can build the mindsets and skills to interact with this strange and ever-changing thing. Returning to Ethan Mollick:

There is no list of how you should use this as a writer, or as a marketer, or as an educator. They [the developers] don’t even know what the capabilities of these systems are. They’re all sort of being discovered together. And that is also not like a tool. It’s more like a person with capabilities that we don’t fully know yet.

We must play with the GenAI to discover new capabilities, not just replicate templates for uses others have developed.

What We Should Teach

At some level, the question is not WHAT we should teach but HOW we teach. We have in previous publications argued for a form of open-ended design-based pedagogical approaches that we have called Deep-Play. Briefly, deep-play refers to the immersive engagement with the intricate problems of pedagogy, technology, and their interrelationships. Through deep-play, educators transition from being passive technology users to active designers who creatively repurpose tools and artifacts to achieve their goals and desires. The core objective of learning technology through design courses is to shift away from a utilitarian view of technology, fostering a flexible, context-sensitive, and learner-driven approach. We have argued that learning to use technology for teaching requires adopting a new mindset that prioritizes developing adaptable strategies for deeply considering the role of technology in education over merely mastering specific tools.

We believe that these same strategies and mindsets apply to generative AI.

0 Comments