Anyone who works in the area of social design knows how important it is to develop a systems-oriented mindset and how difficult it is to do so. One one hand, we know that sustained change is possible only when we work at the level of systems not individuals and one-off projects. One the other hand, systems thinking is complex, and often difficult to grasp and explain. This is a challenge we face on a regular basis at the Teachers College and the Office of Scholarship and Innovation (OofSI) as we seek to instantiate principled innovation in educational contexts.

Aside: For some examples of the kind of work we are engaged in see this post by my colleague Brent Maddin: Field of Teams and my earlier post about our work in the Kyrene School District or read this series from our Dean, Carole Basile).

So I am always on the lookout for good accessible examples that can help me and others understand the value of systems thinking. I recently came across two examples that do the job really well.

The first one is a blog post by Aaron Swartz published back in 2012, titled: Fix the machine not the person. In this post Aaron describes an unique experiment where GM and Toyota collaborated on rejuvenating a failing car factory in Fremont. What is amazing about this story is not just what changed (a factory went from being a disaster to being a success) but what did not. What did not change were the people who were working at the factory. This is a must read story that speaks to how a change in systems and values can transform how people connect and work together.

Aaron bases his post on an This American Life episode (here) but also adds to it by speaking to an important psychological idea, a blind-spot that we all suffer from, what is known as the Fundamental Attribution Error. The Fundamental Attribution Error posits that, we, humans, attribute other people’s errors or mistakes to their personality, not their situation. Of course in our own case, any errors we make are attributed to contextual factors not our inherent personality. Here are some key paragraphs from his post

Our natural reaction when someone screws up is to get mad at them. This is what happened at the old GM plant: workers would make a mistake and management would yell and scream. If asked to explain the yelling, they’d probably say that since people don’t like getting yelled at, it’d teach them be more careful next time.

But this explanation doesn’t really add up. Do you think the workers liked screwing up? Do you think they enjoyed making crappy cars? Well, we don’t have to speculate: we know the very same workers, when given the chance to do good work, took pride in it and started actually enjoying their jobs….What worked wasn’t yelling, but changing the system around you so that it was easier to do what you already wanted to do.

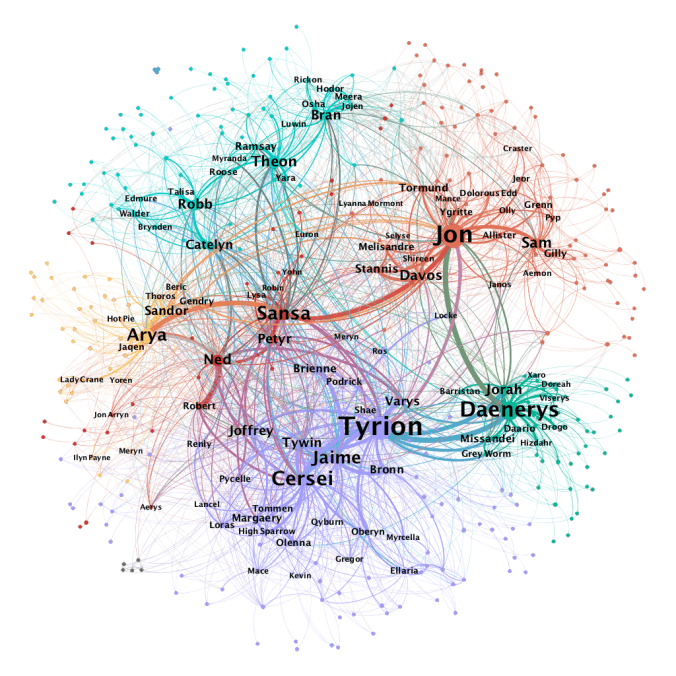

The second blog post is more recent and by one of the most influential scholars about the new world of the Internet and social media: Zeynep Tufekci, associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Information and Library Science. In a post dated May 2019, Tufekci connects TV shows like Game of Thrones and The Wire with the fundamental attribution error (without naming it directly), the importance of thinking sociologically to how we should be thinking about modern technology and its discontents.

The post is titled: The Real Reason Fans Hate the Last Season of Game of Thrones and the subtitle “It’s not just bad storytelling—it’s because the storytelling style changed from sociological to psychological” alludes to the argument she is making. But don’t take my word for it, the post is worth reading in its entirety. Here are some key quotes, but again, read the entire post for yourself:

When someone wrongs us, we tend to think they are evil, misguided or selfish: a personalized explanation. But when we misbehave, we are better at recognizing the external pressures on us that shape our actions: a situational understanding. If you snap at a coworker, for example, you may rationalize your behavior by remembering that you had difficulty sleeping last night and had financial struggles this month. You’re not evil, just stressed! The coworker who snaps at you, however, is more likely to be interpreted as a jerk, without going through the same kind of rationalization. This is convenient for our peace of mind, and fits with our domain of knowledge, too. We know what pressures us, but not necessarily others.

That tension between internal stories and desires, psychology and external pressures, institutions, norms and events was exactly what Game of Thrones showed us for many of its characters, creating rich tapestries of psychology but also behavior that was neither saintly nor fully evil at any one point. It was something more than that: you could understand why even the characters undertaking evil acts were doing what they did, how their good intentions got subverted, and how incentives structured behavior. The complexity made it much richer than a simplistic morality tale…

Another example of sociological TV drama with a similarly enthusiastic fan following is David Simon’s The Wire, which followed the trajectory of a variety of actors in Baltimore, ranging from African-Americans in the impoverished and neglected inner city trying to survive, to police officers to journalists to unionized dock workers to city officials and teachers… Interestingly, the star of each season was an institution more than a person. The second season, for example, focused on the demise of the unionized working class in the U.S.; the fourth highlighted schools; and the final season focused on the role of journalism and mass media.

In my own area of research and writing, the impact of digital technology and machine intelligence on society, I encounter this obstacle all the time. There are a significant number of stories, books, narratives and journalistic accounts that focus on the personalities of key players such as Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Jack Dorsey and Jeff Bezos. Of course, their personalities matter, but only in the context of business models, technological advances, the political environment, (lack of) meaningful regulation, the existing economic and political forces that fuel wealth inequality and lack of accountability for powerful actors, geopolitical dynamics, societal characteristics and more.

These two posts brought home to me just how complex these issues but yet, how taking a systems approach allows us to not just ask the right questions but also to come up with nuanced and thoughtful answers to the challenges we face as educators. That as educational designers we need to take a systems view, not focusing as much on the individuals within the system as being good or bad actors, but rather at the way the system is designed (the contexts and influences, the culture and incentives) that more than anything else determine the outcomes.

0 Comments