Note: I wrote and submitted this piece as an op-ed to the Indianapolis Star to be published on April 14, 2023, exactly 3 years after they had published Gilbert Daniels’ obituary. It would have helped set the record straight about his amazing contribution to the world we live in, but sadly I never heard back from them. My one-sided correspondence with them is included at the end of this post, just for the record.

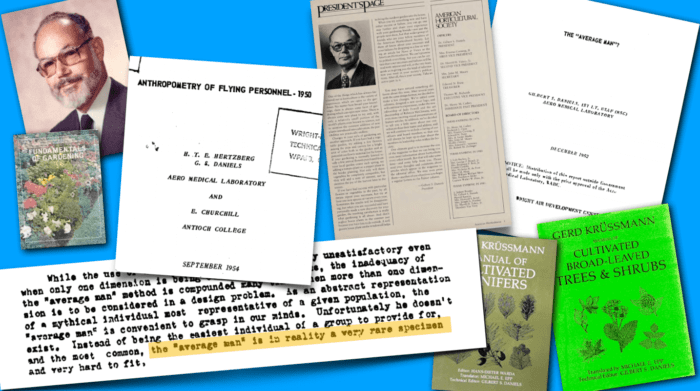

Gilbert S. Daniels, aged 92, passed away peacefully at the Kimes Nursing and Convalescent Center, in Athens Ohio on April 14, 2020 (almost exactly 3 years ago). His obituary, published in the Indianapolis Star described his lifelong love of horticulture and botany, that began when he was just 7. At 17, he won the prestigious Westinghouse Scholarship with his paper on the future uses of plants in pharmacology. He got a degree from Harvard, spent a few years in the Air Force, moved to private industry but finally went back to his first love, botany, receiving his doctorate from UCLA. He ended his professional career as director of the Hunt Botanical Library at Carnegie Mellon but continued his connection to horticulture after retirement, maintaining a garden in Indianapolis, photographs of which were deemed worthy of being archived by the Smithsonian.

It was clearly a life well lived—a talented individual with a full and rich life, following his passion and interests. But what the obituary ignored was Daniel’s important contribution to the world that we all inhabit. And this happened in the few years he worked in the Air Force at the Wright Patterson Base in Dayton, Ohio. The work that he did there changed not just the Air Force, but in some ways it has touched all of our lives.

A bit of context may be in order. In the late 1940’s, the US Air Force was facing a major problem. Many of its planes were crashing for reasons labeled as “pilot error,” with no obvious malfunctioning in the mechanics/electronics of the planes. The Air Force ultimately realized that the design of the cockpit was to blame, possibly because it was based on averages of measurements taken from male pilots back in the late 1920’s. They wondered if people had grown bigger and that the design of the aircraft needed to be updated to match the measurements of a “new” average.

Leading this work was 23-year-old Lt. Gilbert S. Daniels, fresh from his degree at Harvard. As part of this project, he measured approximately a hundred different physical dimensions of over 4000 airmen. As he studied the data, however, Daniels began to wonder about just how many pilots actually fit the so-called “average.” To test this, he selected ten key averages, such as height, weight, arm length, hip circumference and so on to see how many airmen would fall into the average in these categories. What he found was surprising—not a single pilot, of the 4,063 measured, fit in the average range on all ten dimensions (let alone the 100 different dimensions he had measured). He realized that it was virtually impossible to find an ‘average man’ in the Air Force population.

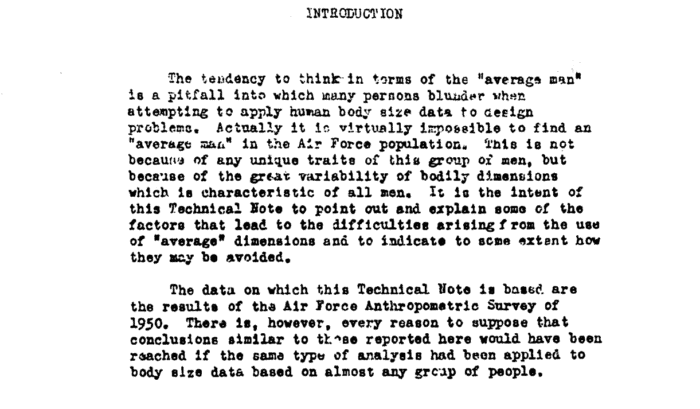

Excerpt from “The ‘Average Man’?” by Gilbert Daniels (link to pdf at the end of this email).

Daniels’ great insight was that this was not due to anything unique in this group of men, but rather because of the inherent variability in bodily dimensions characteristic of all people. He wrote:

The “average man” is a misleading and illusory concept as a basis for design criteria and is particularly so when more than one dimension is being considered.

Gilbert Daniels

Essentially, Daniels’ suggested that if you design for the average, you design for no one. This is because we all have “jagged profiles,” i.e., physical measurements that never smoothly and perfectly line up with every single average measure. If you have an average torso, your hands maybe longer or shorter than average; the same for weight or height or any of the 100 variables he measured.

Moreover, if this was true of a somewhat homogeneous group (white men who were air force pilots in this case) the results would be even messy if expanded to include all people. Simply including women pilots, for instance, would have complicated matters up even more.

Daniels’ insight sparked transformative changes in the design of aircraft cockpits, shifting the focus from meeting the needs of a mythical average pilot, to creating flexible and adaptive designs to fit the needs of individuals’ “jagged profiles.” This is what led to adjustable seats, flight suits, and helmet straps, as opposed to a one-size-fits-the-average approach. And in time this insight spread through all aspects of design, leading to things we take for granted today: adjustable car seats, bike helmets, and much more. In some critical ways, Lt. Daniels’ insight transformed the designed world that we all live in to become more adaptive and adaptable for the rich variation of humanity.

Some images from Gilbert Daniels’ life: Books he wrote or edited, his reports for the air force etc.

As must be clear, this has significant implications for us as educators, where the attributes we are interested in go beyond the physical, and the easily measurable, to more intangible constructs such as talent, interest, grit, cultural and social capital and more. This is exactly how I came across Gilbert Daniel’s seminal insight, while conducting research on designing educational software and educational systems that meet the needs of ALL learners. For too long the design of curriculum and educational policy has focused on this mythical idea—the average learner. This is something we are fighting against even today. As Harvard professor Mike Rose has written, speaking of Daniel’s work: “if we ignore jaggedness, we end up treating people in one-dimensional terms”

It is not just his obituary in the Indianapolis Star that ignores his work in the air force. His obituary, in the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation Spring 2021 bulletin, does the same, just mentioning in passing his work as a physical anthropologist for the air force, encapsulating in just one sentence his seminal contribution to our world:

He worked as a physical anthropologist for the Air Force and then joined the private sector to work in the early computer industry.

On this date, in April, three years from Gilbert’s passing, it may be appropriate to recognize his fundamental contribution to the world we live in today. Daniels may have had an illustrious career as a horticulturist, but it is his insight on the myth of the average may have been his greatest contribution. We should remember him every time we adjust our car-seats, tighten the strap on our bike-helmets, or turn on close captioning on our TV’s (despite having pretty good hearing). What he discovered and wrote about in his reports drives conversations and informs education and design even today.

Addendum I

- Two original documents from Gilbert Daniels’ time in the air force. It is actually quite amazing to read these documents – specially The “Average Man”?

- Anthropometry of Air Force Flying Personnel (1950) (published 1954)

- The “Average Man”? (published 1952)

- Article by Todd Rose: When the US air force discovered the flaw of averages (there are some really interesting details in this article about Gilbert Daniels’ work when he was at Harvard that prepared him to question the myth of averages and how other’s saw similar data and came to very different conclusions.)

- TEDx talk by Todd Rose: The myth of average

- A great episode of the 99% Invisible podcast on this topic: On Average

- YouTube Video by Stand-up Math: Does the average person exist.

- Gilbert Daniels devoted a significant part of his live to horticulture and botany, He had a particular interest in Heliconia, large tropical flowers native to Central and South America and some islands of the South Pacific. Heliconia are regarded as being among the great botanical beauties of the natural world. Gilbert Daniels work is recognized here here. A few of the were named after him, in recognition of his work including Heliconiana gilbertiana and Heliconiana danielsiana.

Addendum II

I wanted this piece to be published in the Indianapolis Star on April 14, 2023, exactly 3 years after his obituary was published. So I sent an email to their op-ed editor on March 1, 2023 and then to the editor on March 27. I never heard back from them. I even tried calling them but never could find a phone number which led me to a real person.

Here is the first email I sent:

Date: March 1, 2023

From: Punya Mishra

To: oboyd[AT]gannett.com

My name is Punya Mishra and I am a professor at Arizona State University in the College of Education. You can find out more about me at my website https://punyamishra.com

I am submitting an opinion piece for the Indianapolis Star, based on an obituary of Dr. Gilbert Daniels, who lived in Indianapolis post retirement, that was published on April 14, 2020 (https://www.indystar.com/obituaries/ins106018). In my piece I seek to address a gap in the obituary—something important that was missed. His obituaries (and I have read a few) do not mention what I think is his greatest contribution – something that has changed the world we live in in profound ways. I think it would be cool to commemorate his life, legacy and contribution but publishing something like what I share below around April 14, 2023, three years after his passing.

~ punya

And my second message.

Date: March 27, 2023

From: Punya Mishra

To: cindi.andrews[AT]courierpress.com

Cindy –

My name is Punya Mishra and I am a professor at Arizona State University in the College of Education. You can find out more about me at my website https://punyamishra.com

A few weeks back I had submitted an opinion piece for the Indianapolis Star, based on an obituary of Dr. Gilbert Daniels, who lived in Indianapolis post retirement, that was published on April 14, 2020 (https://www.indystar.com/obituaries/ins106018). In my piece I seek to address a gap in the obituary—something important that was missed. His obituaries do not mention what I think is his greatest contribution – something that has changed the world we live in in profound ways. I think it would be cool to commemorate his life, legacy, and contribution by publishing something like what I share below around April 14, 2023, three years after his passing.

I haven’t heard back – so thought I would followup with you and see if this is of interest. I think Dr. Gilbert made a huge difference in the world we live in today – and should be recognized by the place where he lived last. Either way, I would appreciate a response.

Sincerely

~ punya

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing Punya. I linked here from the MLFTC newsletter. Glad to learn of Gilbert Daniels’s impact and important research findings here. Given the eugenics movement that was prominent in the early 1900s, his research findings were a challenge to frameworks of his time, and underscore the importance of broadening understanding human diversity.

Thanks Lirio, for your comment. You make a really important point.

I really like this! This goes well beyond the average post!

Thank you Peter.