The fictions we create (& how they create us)

This is a story about a multi-year quest and its resolution (thought not necessarily in the way I was expecting). It is also a story about stories: stories in books and stories that we make up. And how these stories, in turn, make us… Hope you enjoy it.

In the beginning was a story.

A story I had read many decades ago, possibly when I was in high-school or college.

A story that connected with me, deeply. A story that I shared with others as an example of certain deeper philosophical beliefs I held about nature and nurture and education and learning. Because you see, in my mind, this story was an almost perfect encapsulation of my beliefs—and made the point much better than any conceptual discussion. And, from other people’s responses, when I shared it with them. It was just not me, the story resonated with them as well.

The only problem was that I had completely forgotten the title of the story, the collection I had found it in. All I remembered was that it was a story by Ursula le Guin.

This is the story of that remembered story and my attempts to find the original. And how finding the original raised more questions about the stories we tell ourselves—about our identity and who we come to be.

It isn’t that I hadn’t tried to find the original. Over the years I had, off and on, made many attempts to find the story, posting on Le Guin related Reddit boards, sending emails to science fiction authors and Le Guin experts, contacting librarians at ASU and elsewhere. But to no avail.

After many such intermittent efforts over the years, I decided to get serious about locating it. This was prompted by my listening to an episode (The Case of the Missing Hit) of the podcast Reply All in which the hosts helped a listener track down a song they had heard in their youth but never again since. I decided to write a blog post and seek the help of the Internet (and possibly the Reply All people as well).

As a part of my effort for this story, I wrote and pinned a blog-post on my website titled “Help me, find a story by Ursula Le Guin” in which I described the story (as I remembered it) and asked for help.

Here is the story as I remembered it…

It was a story about a world (a planet?) like ours, but different. I remember it as being this somewhat bucolic world, yet technologically advanced. None of this was explicitly laid out but you could infer from how the world was described.

The important thing to know about this world was that young people (once they reach a certain age) were assigned a profession based on the results of an aptitude test administered by the government. And once your profession was assigned, you moved away from your family, the community you grew up in, to where ever the job required you to go. I think it was implied that there were many different “professional” communities in this world—communities of people who did the same job. Communities of bureaucrats and artists, technologists and story-tellers, miners and engineers.

The story, as I remembered it, was about this sensitive young man who had always wanted to be an artist. That was all he ever wanted to do. He believed he had the aptitude, the talent and the commitment to be a great artist. And he looked forward, with great excitement, to hanging out with others with the similar interests and creating great art.

The results of the test, however, did not come out the way he had expected. He was told that, according to the test, the profession he was best suited for was to be a miner. He knew this was a mistake and he appealed the decision. But he was told that the test had never been wrong and that the decision was final. With no choice, he ended up in a mining town/planet/island (I am not sure I remember exactly) and, as he expected, he hated it. In the beginning he kept sending in appeal after appeal, which keep getting turned down, over and over. He was sullen and angry, hating the people around him but had no choice but do the work he was assigned. It was difficult, brutal, physical work, far from the sensitive world of artists and ideas he had so hoped to be a part of. He did not like the people there in the mining community, finding them rough, and loud and lacking in sophistication. The miners spent their days working hard long hours and then filling the rest of the time drinking and boisterous merry-making.

His was a lonely, solitary existence, doing his job but keeping to himself for the most part. The others in the mining community did not understand him at all. They found him aloof and arrogant and often made fun of him and his ways.

Over time however, he stopped appealing to the ministry and began to accept that this would be his life. He slowly adjusted to the place, its roughness and brutality – and made a life. The others in turn, came to accept him as well, as an idiosyncratic but harmless person.

As the story goes, one day, while working in the mines, he discovered a strange mineral that intrigued him in the way it glowed and shimmered when cut with the mining lasers. He brought some of it home and started playing with it, with no particular goal in mind, and ended creating some kind of sculpture (my recollection is fuzzy about what exactly he created) that he found interesting. It was something that gave him a bit of pleasure—a respite from his daily routines. And that was how he spent his off-hours, tinkering with this new material, learning its secrets and creating these “things.” He did not see these creations as art, but just as something to do, to fill the empty evenings.

One day someone, possibly one of his neighbors, saw one of these creations and asked if they could keep one. Since he had no particular attachment to these creations, or any use for them, he said yes. Over time, others came to ask for pieces as well and he obliged. He really didn’t care that much for these creations. He enjoyed making them and was pleasantly surprised that people liked them.

Life went on. Years went by.

Till one day. He received an urgent message from the ministry. A deeply apologetic message. Acknowledging an error. An audit had revealed that they had erroneously assigned him to be a miner. He was, and his tests showed that, he should have been an artist. Something like this had never happened before. But they were ready to make amends. He would be, immediately, taken to his rightful place, among the artists. His life-long dream would finally come true. So, he was shipped off, immediately, to this artists paradise. And as far as the ministry was concerned a dreadful wrong had been corrected.

Except that, very soon, the ministry received a new appeal from him—a request to be sent back to the mining colony/community.

It turned out that he was miserable in the artist community. He didn’t like these people. He found their conversations meaningless and abstract, lacking any connection to the real world. He missed the rhythms of his life in the mining community, the rough honesty of the people there, and the space he had built for himself with them.

This was not possible, the ministry said. The test had been reviewed, and the right decision had been made (though they were deeply apologetic about the error the first time around). His new appeal was turned down. This IS where you belong.

And, that is all that I remember. I do not remember how it ended—possibly with my protagonist stuck in this new world.

Growing up, this story resonated with me deeply, and has stayed with me all these years, maybe even influencing how I approach my work as an educator. It speaks to this complicated relationship between innate talent and experience and how both of them play critical roles in making us who we are. That our identities are results of this complex interplay between what we bring to the table, and what opportunities we receive. And that happiness is complicated, and unpredictable.

It also spoke to me of the fact that there is so much talent in this world—that often goes unrecognized and unappreciated, as seeds planted in dry sand. As Steven Jay Gould wrote:

I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.

How many Ramanujan’s, I often wondered, are there in the world who never found a Hardy who could recognize their genius.

At another level, this story also gives hope—that even in the most inhospitable and unexpected of contexts, individuals can find a way, a way to support their talents, to let this potential emerge. That who we are (or become) is that amalgam of what we come to the world with and the experiences and opportunities we are given.

Once I had posted the note on my website, I tweeted it, even tagging the producers of Reply All hoping they might pick it up or at the very least re-tweet it. They never did, but my post was read by a few people, and retweeted by others…

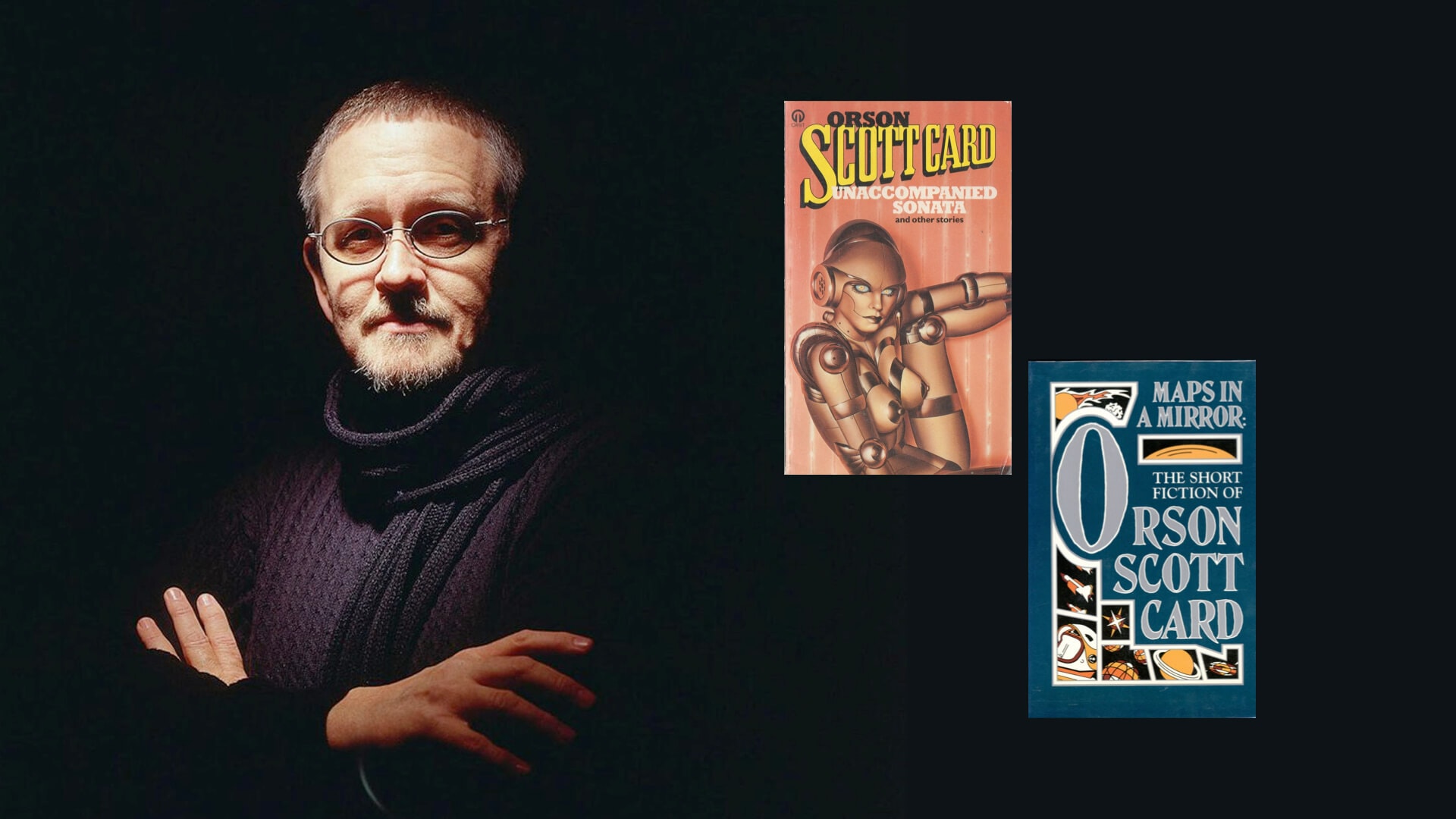

And then, I received a reply from someone on twitter, a stranger, who wrote to say that my synopsis reminded them of a story they had read, not by Le Guin, but rather by Orson Scott Card.

That gave me pause particularly because I was so utterly confident of this being a story by Le Guin. If anything, that was one thing I was certain about. In my head it had Le Guin’s style written all over it.

That said, their point also sounded plausible. At that time in my life, I had been reading a lot of science fiction, and Orson Scott Card was one of the authors I had been reading.

And they went further adding that my rendition of the plot reminded her of a particular story, a story titled “The Monkeys Thought ‘Twas All in Fun.”

A bit of digging around on the internet informed me that this story had appeared in two of Orson Scott Card’s short story collections, Unaccompanied Sonata and Other Stories and Maps in a Mirror. The first of these two books seemed very familiar to me, particularly when I began reading its table of contents, and excerpts of the stories on Wikipedia. I knew that I had read this book. But there wasn’t enough information about the story I was interested in. I needed to find the story itself.

Which I did (thank you Internet). And within minutes I knew I had been mistaken. It was not a Le Guin story I had been looking for, but rather, one by Orson Scott Card. Which explained why I had such a difficult time finding it. I had been looking in the wrong places, entering the wrong search terms.

What is funnier still is that, even though I know better, I still have almost a palpable sense of holding a Le Guin short story collection in my hands, and seeing the words on the page. The font on the page, of the scanned pdf that I had found, looked wrong, did not match the image in my head.

Furthermore, as I dug into the story, I started finding strange discrepancies between what I remembered reading and the story I was reading at this moment. Enough of the details were similar that it was clear this had to be the story I had read. Yet…

For starters, the Orson Scott Card story was not a stand-alone story, as I thought it was, but rather a story (almost a parable) within a larger narrative. Incidentally, the eponymous monkeys, are in the larger narrative… none of which had stayed with me.

It was also a far more pessimistic story, darker, more cynical, with an undertone of violence which also came as a surprise. It lacked the grace in the language, the flow, that I had imagined it had—partly because, I think, I had attributed it, in my head, to Le Guin and her style of writing!

I had also created crucial details, details that I was certain I had read, but were not in the original. For instance, in the story I was reading, the main character (who I now know was named Cyril) was not destined to be an artist—but rather a furniture maker.

Then there were the details I had made up. For instance, I had entirely made up the part about his bringing back stuff from the mines and making abstract sculptures with them. All that stuff about lasers and glowing minerals, the intricacy and complexity of his creations, that I remembered—all made up. None of these details were in the story by Orson Scott Card.

I had also forgotten that the ministry was represented by an individual (an important character in the story). In my version, the ministry was more faceless and bureaucratic than this individual, who though officious was also (within limits) kind to Cyril.

Most importantly, I had forgotten a very important character, a character who was critical to the Orson Scott Card story. It was a women he had loved when he was young, and she had loved him in return. They were separated when he was sent to the mines. In fact, on reading the story again, I realized that the main theme of the story not about talent and opportunity. The story was actually about the tragedies that befall not just us, but others around us as well, when key decisions are made for us, when choice is taken away from us. And that there is no going back.

And there is a brutality to the original story overall that I had minimized or forgotten. But it was the ending, more than anything, that I had completely repressed. Let me just say, it does not end well for the woman he loves (and the protagonist).

The original story was a tragedy–not this mixed, “there is hope even in the most dire of circumstances” theme that I remembered.

It was almost as if I had missed the point of the original story entirely.

We know a lot about how our memory functions, and on how memories are actually constructed rather than brought forth from an immaculate recorder in the mind. We also know about the kinds of memory errors we make: how our mind fills in details that don’t exist, erasing others that don’t fit for one reason or another. Remembering is an act of construction and meaning-making as much as it is recollection. In fact, one of my first published empirical research articles has to do with the role of theories in memory, building on earlier work on schemas and mental models.

I was struggling to understand why, in this case, I remembered certain details, made up others and forgot a bunch. I do know why the story was important to me. It spoke to the complex relationship between talent and context which both allows for and constrains growth and development, and at the end of the day, makes us who we are. In that sense this story has been deeply influential—which is why I remember it so well and also why I have shared it with others, students and other academic colleagues, over the years. Which is also why I set out on this quest in the first place.

But in my remembering and retelling of the story, I had altered it, in my mind, unbeknownst to me, in ways that fit the broader theory I was developing. Thus, this story was both the “germ” of my theory of nature/nurture, and in my “creative” reconsidering/remembering the story also was a “result” of the theory.

Which came first? Do I remember the story the way I do because I had a predilection towards these ideas? Maybe—why else would this particular story stay with me? Or, did my creative remembering help “confirm” a world-view that emerged later, about the relationship between innate talent/propensities/interests and its flourishing in the world.

I also wonder about whether it matters when I read the story—where I was in my life at that time? As far as I can remember, I read this story while I was in college, struggling to complete an engineering degree that I hated. (I have written about these years in a previous post titled My favorite failure.) My interests were wider and broader, including but not limited to science, literature, film, art and poetry, none of which were valued at this school. Maybe it was my struggle to find a balance between these interests, and the world I was forced to live in, that made this story resonate so? Maybe I hoped that I would, just as the main character in the story did (at least the way I remembered it), find a way to balance my interests and my situation and find a way forward.

Maybe that’s why I conveniently forgot the tragic ending the original story had. That would have been too much for me to bear.

In some sense what I remembered (essentially what I created in my head) was to confirm something that I wanted to believe.

At the end of the day, I am glad my years-long quest has been resolved. But at another level, I am a bit sad, because, now having read the original, I realize that the story I had created in my head, was so much “better.” Better because it fit so well with my narrative, this theory I had in my mind and which “my” story made an argument for so beautifully and powerfully.

In some sense, this story, the one I am telling now, is really about two made-up stories, two pieces of fiction. The first is the piece of fiction that I read decades ago, written by Orson Scott Card, and the second is the fiction I created in my head inspired by what I had read decades ago. And over time, I had unknowingly, embellished it, and tweaked it, added some stuff, removed other bits, and made it my own.

And I also realize, now that I have rediscovered the “real” story, it will work its way into my brain. The original Orson Scott Card version, will slowly, but surely, replace my story, the one I had made up. In fact I am sure that is happening already. I am losing the beautiful details I had constructed (some clearly out of whole cloth) and am forced to acknowledge the uncomfortable ones I had pushed away. I can feel my story “fade away”—and that is sad.

But then again, I have this new story now—a new piece of fiction, about two pieces of fiction, a meta-story as it were, about memory and identity, and so much more. And that is satisfying in its own way.

0 Comments