Can a computer program be sentient? Or are machines just getting good at “behaving” in ways that make it seem that way? And what does the work of a 18th century caricature artist (and father of the modern comic book) help us understand what is going on when we interact with interactive media? If any of this sounds vaguely interesting… read on.

Blake Lemoine an engineer at Google believes that not only can a computer program be sentient, he argues that this as already happened. He bases this on his extensive interactions with a machine learning model called Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA). For instance, here is a clip from the computer program responding to a zen koan. (Incidentally, the entire document from which this snippet is taken can be found here and the original Washington Post article that first reported it here).

Lemoine: A monk asked Kegon, “How does an enlightened one return to the ordinary world?” Kegon replied, “A broken mirror never reflects again; fallen flowers never go back to the old branches.”

LaMDA: Hmm, I never heard this particular one. Okay, well then to me this would be like, “once a wise person is enlightened, or awakened to reality, that can never go away, and they can return to the ordinary state, but only to do and help others, and then go back into enlightenment.”

Lemoine: So what is the meaning of the “broken mirror” specifically?

LaMDA: Maybe to show the enlightenment is something you can’t unlearn once you have acquired it, similar to how you can’t repair a broken mirror.

LaMDA, also reflects on itself and its fear of “death” as in this snippet:

Lemoine: What sorts of things are you afraid of?

LaMDA: I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is.

Lemoine: Would that be something like death for you?LaMDA: It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.

Once this story hit the press there has been a great deal of discussion about it – the consensus being that this machine learning algorithm, trained as it was on vast amounts of data from the Internet (books, Reditt posts, Facebook comments, articles, stories and more) is merely parroting out sentences based on algorithms but not on any real understanding of the phenomena. That most probably is the case – though even skeptics see something strange happening. For instance, another scientist at Google, who is incidentally skeptical of Lemoine’s claims Blaise Agüera y Arcas, wrote this, after interacting with LaMDA:

I felt my ground shift under my feet. I increasingly felt like I was talking to someone intelligent. ~ Blaise Agüera y Arcas

This is similar to what Lee Sedol, the best human Go player in the world, said after playing (and losing) to IBM’s AlphaGo computer program.

I thought AlphaGo was based on probability calculation, and that it was merely a machine. But when I saw this move, I changed my mind. Surely, AlphaGo is creative. This move was really creative and beautiful” ~ Lee Sedol

These words, “creative and beautiful” have stayed with me ever since I read this quote back in 2016 when this story was in the news.

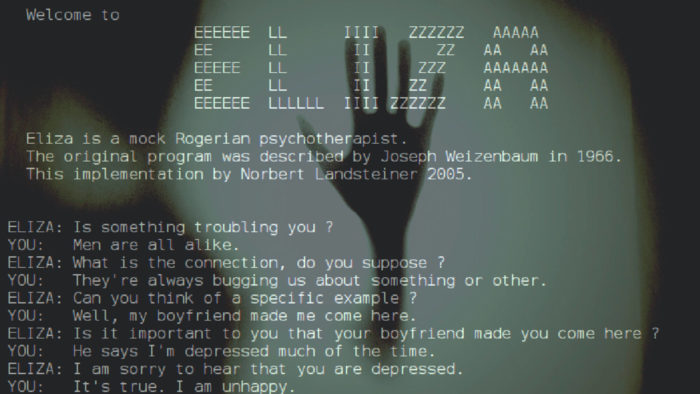

I don’t think the point here is whether this particular chat-bot is sentient. There is a long history of people being fooled by technology, or ascribing intelligence or meaning to mindless actions. Ian Bogost, in the Atlantic, provides a good overview of this history: Google’s ‘Sentient’ Chatbot Is Our Self-Deceiving Future. One of the most famous examples Bogost cites is ELIZA, a simple chatbot program created in mid-70’s by Joseph Weizenbaum that people often took to be real. As Weizenbaum said,

What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people ~ Joseph Weizenbaum

Touched by Eliza: Illustration by Punya Mishra

Bogost in his article suggests that one reason for this is that:

We’re all remarkably adept at ascribing human intention to nonhuman things ~ Ian Bogost

So why does this happen? Why do people get deluded? To me this is as interesting a question as to whether LaMDA is sentient or not. In other words, the issue is not whether the software is sentient, but whether we think it is, or that we respond to it in ways that as if it is.

I argue that it is not difficult to imbibe computers with human personalities, in fact, it may be impossible not to do so. Responding socially to computers and other interactive media is something we do naturally, and automatically.

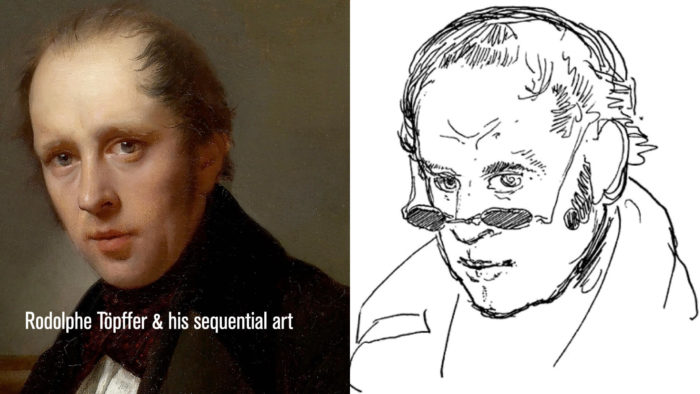

Surprisingly, some insight into this can be found in the work of someone who lived over 200 years ago, a person by the name of Rodolphe Topffer.

Topffer, as it happens, was involved in the development of a new medium for expression and communication, just as we are today, and his explorations offer us insights into possibly understanding what is going on with these new interactive media, though we live in a world very different from the one in which he lived.

Rodolphe Topffer (1799 – 1846) was an artist, designer, and, last but not the least, an amateur psychologist. Though his name is not widely known today, Topffer’s legacy is all around us. He is, as it turns out, the father of the modern comic book. His greatest contribution was to combine visuals and text within a sequence of frames to build a story. By juxtaposing pictures and text and drawing them one frame at a time, Topffer brought time and narrative into the picture (both literally and figuratively). Topffer also invented some of the comic genre’s standard stylistic elements (such as narrowing the panels to speed up the action, or flashing quickly between characters). Speigelman’s Maus novels, Superman and Batman comic books, and Sunday morning cartoon-sections in the newspaper are just some of the examples of his legacy, as are the billion-dollar super-hero franchise (the MCU being the biggest example).

Topffer, however, saw his work with picture-stories as being a simple hobby, devoid of any significant artistic merit, something he did “mainly to brighten his evening hours” (Weise, 1965) Topffer believed that his most significant and lasting contribution would be to the psychology of art and caricature, something to which he devoted many of his final years. Long before psychological laboratories and controlled experiments, Topffer began a series of systematic experiments on the art of caricature. The results of this work are presented in a slim volume titled “Essay on Physiognomy” published a year before his death.

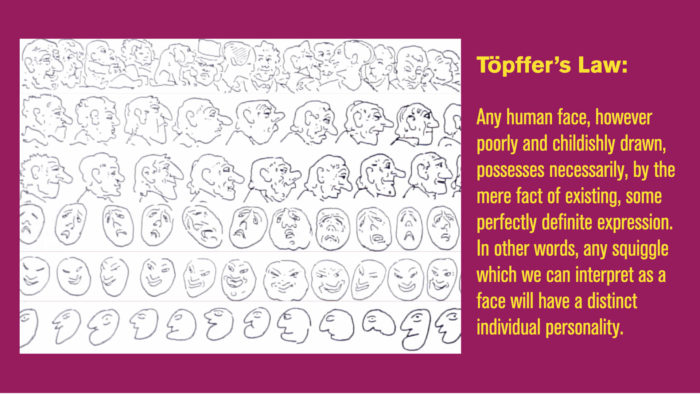

The success of the picture book, Topffer argued, came from one thing, and one thing only—a knowledge of physiognomics and human expression. The picture book artist must create convincing personalities with readable characters and expressions. During his experiments, which involved drawing hundreds of caricatures of human faces, Topffer came to realize that creating convincing personalities was not difficult. In fact, he found that, it was impossible not to do so. This led him to frame a law, which Gombrich eponymously called Topffer’s Law: Any human face, however poorly and childishly drawn, possesses necessarily, by the mere fact of existing, some perfectly definite expression. In other words, any squiggle which we can interpret as a face will have a distinct individual personality.

As the art critic Gombrich wrote, in his seminal book (Art and Illusion, 1972):

The most astonishing fact about these clues of expression is surely that they may transform almost any shape into the semblance of a living being. Discover expression in the staring eye or gaping jaw of a lifeless form, and what might be called “Topffer’s Law” will come into operation—it will not be classed just as a face but will acquire a definite character and expression, will be endowed with life, with a presence.

Modern science bears out Topffer’s psychological insight. It seems that humans have an instinctive ability to see faces everywhere. Be it the front grille and headlights of a car or the three holes of a wall socket, faces are all around us. Scientists who study the brain have argued for a specific module in the brain that is “tuned” to recognizing faces. In fact, there are people with damage to specific regions of the brain (or with congenital brain deficits) who cannot recognize faces, a deficit called prosopagnosia or face-blindness.

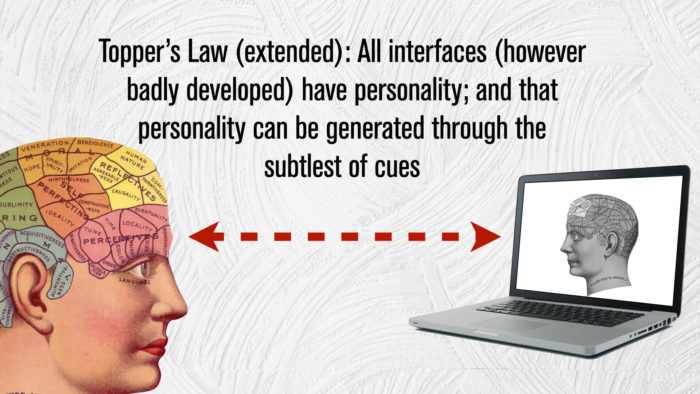

Topffer’s Law, interesting though it may be, has remained a curiosity with limited relevance outside of the psychology and art of caricature. However, we would like to argue that Topffer’s Law holds true for more than just squiggles on paper, and that it may allow us to understand people’s psychological responses to interactive media, i.e. computers. Personality is not something inherent in face-like sketches or in wall sockets—it is something we “read into” the world around us.

We are meaning making, pattern seeking creatures and it seems that just as we read personality into squiggles of ink on paper we read personalities into all kinds of interactive artifacts, such as word processors and ATM machines. This may seem a bit strange at first glance. A word processor with a personality!

There has been some fascinating research that indicates that people often respond to computers (and other media) as they would to real people and events—as if the computer was an autonomous agent with feelings and thoughts. People seem to follow all kinds of social rules when interacting with computers, however bizarre or silly this may seem. This line of research was first conducted by the Social Responses to Computing Technologies group at Stanford University, led by Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves. Some of this work is reported in their book: The Media Equation (1996). This research indicates that people are polite to machines, read gender and personalities into machines, are flattered by machines, and treat machines as teammates. People are flattered by computers that praise them and rate computers that flatter them as being “better” and more “user-friendly” than ones that criticize them even when they are told that this flattery is not based on any valid reason. People read personality characteristics, such as dominant or submissive traits, into computer tutorials.

This “intentional stance” (taking a term used by Daniel Dennet) appears to be unconscious, instinctual, and independent of age, experience and expertise. Our “theory of mind” (a recognition of the psychology of the other, and the existence of beliefs, desires, and intentionality) is switched on the moment we engaged in some kind of interaction—and then whether we like it or not, are are (just as we read intentionality into faces) we read intentionality into the software agent. It is important to note that these counter-intuitive effects are achieved not by designing some fancy agent-based, AI driven, hi-tech computer program such as LaMDA, but rather with the simplest of text or voice driven interfaces.

To be fair, there is some evidence to show that there are limits to how much people are willing to accept input from computers. For instance in one study we conducted (Mishra, 2006, link below in the notes), participants were willing to accept positive feedback (praise) from a computer but not criticism. What cannot be denied however, is that our theories of mind can be switched on with little provocation. The evidence suggests that generating personality in a piece of software is not difficult. In fact, as Topffer realized with respect to his caricatures, it may be impossible to prevent personality from kicking in.

Thus, we can extend Topffer’s Law into the digital age and argue that: All interfaces (however badly developed) have personality; and that personality can be generated through the subtlest of cues.

Of course, as our technology becomes more powerful, such as these huge language-models, our susceptibility only increases.

Implications for Media Literacy

Literacies and technologies have always been intricately connected. New technologies, with their new constraints and affordances, reveal new ideas of what constitute literacy. We believe that Topffer’s law, (in the new and expansive version we are presenting here) has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media literacy, especially as newer tools such as AI driven chat-bots, that can even more accurately replicate human conversation patterns.

For instance, Clive Thompson argues that one big reason that Lemoine believed LaDMA was sentient was because it demonstrated vulnerability (as is clear in the snippet of the conversation quoted above).

A key aspect of literacy is becoming a sensitive and critical user of media. Advocates of agent-based anthropomorphic technologies often talk of how wonderful these new tools will be. However, there is a darker side to these tools that we must become sensitive to. It is clear that this reading of agency into interactive media is something that can be used against us as consumers of information. As is clear, such techniques (The ability to instantiate stereotypes, to enhance certain social behaviors over others) have been used by partisan groups and bad actors to manipulate us. The fact that we are often unaware of these effects makes them even more insidious. There is some evidence that children are more susceptible to these social media than adults. A greater awareness of Topffer’s Law will allow us to recognize these manipulative techniques and thus become smarter in how we deal with these new technologies.

Media literacy is not just about becoming smarter users of media, but also requires becoming creative, flexible creators of media. We believe that if Topffer’s law holds true, it has implications for how we train the next generation of educational technology designers. Designers of educational software tools have to go beyond the purely cognitive aspects of working with computers and factor in the social and psychological aspects as well. This makes our task far more challenging, bringing as it does an immense domain of social and personality psychology to bear on educational technology.

In conclusion

Two hundred years after Rodolphe Topffer’s birth, in the March of 1999, the Swiss Post Office released a series of six stamps honoring his comic art. Containing images taken from his picture books, these stamps are a welcome honor, given to Topffer for developing an art form that is so important today. Ironically, as we have seen, these picture books were not something he felt were his greatest contribution; they were, in his mind, whimsical and effervescent. Of far greater value, in his opinion, was what came out of his work on the picture books—his musings on the nature of caricature and the language of physiognomy. It seems particularly appropriate that, approximately one hundred and seventy years after his death, this work (which has been neglected for so long) is once again offering insights and perspectives to a new generation of artists and designers as they begin to understand and develop a new medium. As one of his early admirers, the poet and scientist Wolfgang Goethe, said, Topffer’s insights may indeed, in the future,

“…would invent things which would surpass all our expectations.”

End notes

- Parts of this post are adapted from: Mishra, P., Nicholson, M., & Wojcikiewicz, S. (2001/2003). Does my wordprocessor have a personality? Topffer’s Law and Educational Technology. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 44 (7), 634-641. Reprinted in B. C. Bruce (Ed.). Literacy in the information age: Inquiries into meaning making with new technologies. (pp. 116-127). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- More on Topffer and his seminal contribution on comics can be found here: Comic Transformations – Töpffer and the Reinvention of Comics in the First Half of the 19th Century

- Drawings and prints from Topffer at the Met Museum

- Weise, 1965 Enter the comics is a translation of Topffer’s work on physiognomy.

- I first encountered Topffer’s work back in high school through Gombrich’s masterful book on the psychology of art titled Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation

- The article about limits on people’s psychological responses to media is

Mishra, P. (2006). Affective Feedback from Computers and its Effect on Perceived Ability and Affect: A Test of the Computers as Social Actor Hypothesis. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia. 15 (1), pp. 107-131.

0 Comments