Note: This post was co-authored with Melissa Warr.

I love to talk about design and education. I like to hang out with people who care about design and education. This brings us to TalkingAboutDesign.com, a website/blog created by a group of graduate students (and faculty) at the Teachers College that seeks to explore “design in all its richness.”

At the heart of the website is a framework for thinking about design and its role in education which needs a bit of an introduction (which sort of justifies the length of this post).

Herb Simon, in his book, The Sciences of the Artificial, famously wrote:

Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. The intellectual activity that produces material artifacts is no different fundamentally from the one that prescribes remedies for a sick patient or the one that devises a new sales plan for a company or a social welfare policy for a state.

In one fell swoop, Simon situated design as playing a role across a range of human-centered professions, whether it be graphic design, architecture, medicine, or social policy.

And most relevant to us: Education.

We aren’t the only ones to see education as a design domain (far from it!). For example, in 1992, Donald Schön highlighted how teachers are designers of instruction. Others talk about the design of school buildings, systems, curriculum, and more.

The application of design to education (specifically in its newest avatar: design thinking) has been receiving some significant attention recently. I have written elsewhere about some concerns I have with this trend – but that does not detract in any shape or form the value the I place in bringing a designer’s perspective to education and educational change.

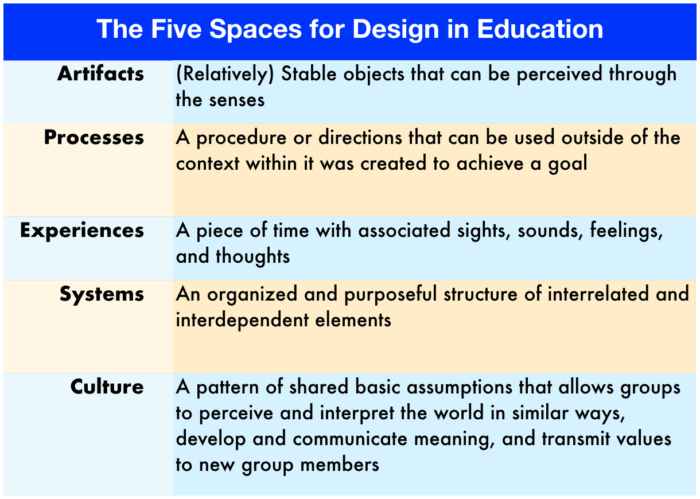

The role of design is complex. Design happens across a range of contexts: from designing textbooks to designing policy; from designing learning experiences to designing admission procedures; from designing professional development programs to designing institutional culture. Thus, design can play out deferentially in different “spaces.” These spaces are connected: they impact one another, and effective design in one space requires an awareness of the other spaces.

Over the past couple of years, we (Melissa Warr, Ben Scragg, others in the Office of Scholarship and Innovation, and a group of doctoral students who call themselves the Talking About Design team) have been working on figuring out the nature of these spaces and applying them directly to education. Preliminary versions of this idea have been presented at conferences (see here and here) but this is an evolving idea, and this blog post is the most current version.

Essentially, we see five interactive spaces where design plays out:

This work builds on and is inspired by previous work by Richard Buchanan and his four-fold classification of orders of design–symbols, things, actions and thoughts or, when seen in terms of the evolution of industries, moving from graphic design to industrial, interaction, and systems design. In each case, the orders are places of invention that allow designers to reimagine problems and solutions. We are also inspired by Golsby-Smith’s work wherein he offered a structure similar to Buchanan, but framed it in terms of the changes in value that designers bring to the process of change. Specifically, as we move from image to strategies and culture, the designer moves from creator to facilitator. This means that designers need a new set of interpersonal skills with an emphasis on communication, facilitation, and systems thinking.

Whereas Buchanan and Golsby-Smith labeled domains of design as “orders,” we avoid the term as it implies a kind of hierarchy between them. As we envision it, each space offers new possibilities for designing, places to create something new or change something that isn’t working. Although the spaces overlap and interact with one another, we distinguish them by where the intended outcome of the design process is focused, whether this is in artifacts, processes, experiences, systems, or culture. In reality, the spaces aren’t as distinct as we are making them out to be; each affects the other in fluid ways. This is where the real power in the framework comes in: we can purposefully move the intention of our design to different spaces in order to create new outcomes—to take new perspectives and find new problems and solutions that can create real change.

What is common across the spaces is design itself. Perkins defines design as “structure adapted to a purpose” and each space then represents an area where we can intentionally create change. Furthermore, there are certain attributes we can point to as being important for designers to possess, regardless of the flavor of design they practice. These are attitudes and mindsets, ways in which designers approach problems, think, and act. These include attributes such as openness, empathy, creative confidence, optimism, a willingness to learn from failure, and a willingness to iterate.

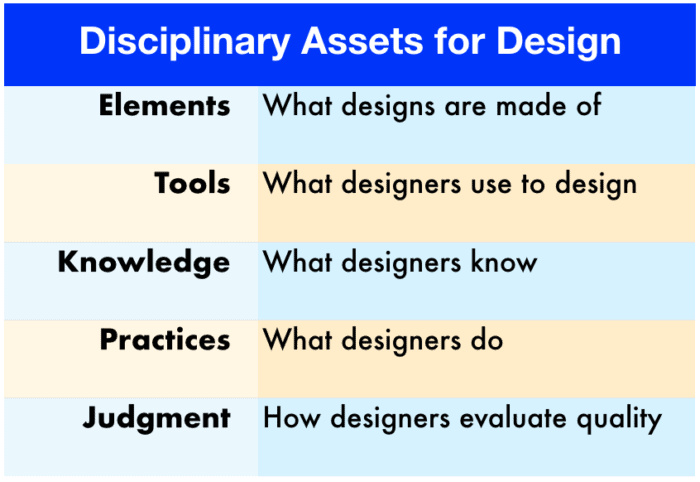

Design also requires working with specific elements and tools, and designers develop knowledge, practices, and judgment that allow them to be effective. These are particular to both the design space and discipline. For instance, within the space of artifact, the kinds of knowledge, tools, practices and judgement required for designing an app are very different from designing school furniture. Similarly, designing a process such as a lesson plan is different in many ways from designing a bell schedule, and so on. Design disciplines have developed a deep reservoir of disciplinary knowledge and practices that give them the unique ability to have a strong impact within their design space.

We have identified five categories common across the five spaces for design that frame the assets each discipline brings to design. In each context, the designer (either individually or in a design team) brings contextual knowledge, practices, and judgment to bear on specific elements and tools. For example, in the case of designing the culture of a university, the elements may be having the right people in the right positions, while the tools may be the development of policy documents, as well as procedures for hiring the right people.

As we design in education, it is important to remain mindful of the rich disciplinary traditions of designers across the five spaces of design. We can draw upon these traditions, including collaborating with expert designers, as we design change in education. At the same time, the five spaces of design framework becomes a conceptual tool to think with—a way to shift perspective and reframe problems and solutions, enabling new ways to approach complex problems. It encourages systemic approaches to innovation in education.

There is a lot more to unpack and build on. One place where this is occurring is the website/blog Talking About Design. This website is the collective effort of a group of doctoral students, faculty and staff at the Teachers College. They are (in alphabetical order by last name): Daniel Brasic, Kevin Close, Luis Perez Cortes, Amanda Riske, Ben Scragg, Melissa Warr, and Steven Weiner. You can find out more by going to talkingaboutdesign.com and we hope you can also engage and participate. We are soliciting questions and answers or just comments. Feel free to jump in.

0 Comments