Ken Friedman, whose article I had used as the basis of my previous posting, From incompetence to mastery, the stages dropped me an email in response to my critique. To provide some context, (you can read my full post here) I had suggested in my posting that it may be inappropriate to label the the highest level of mastery as being unconscious competence. My concern, of course, was with the “unconscious” part – since I felt that true mastery requires a level of reflection, something denied by the word “unconscious.”

Ken wrote that he actually sees examples of unconscious competence everywhere. He went on to say (quoted with permission)

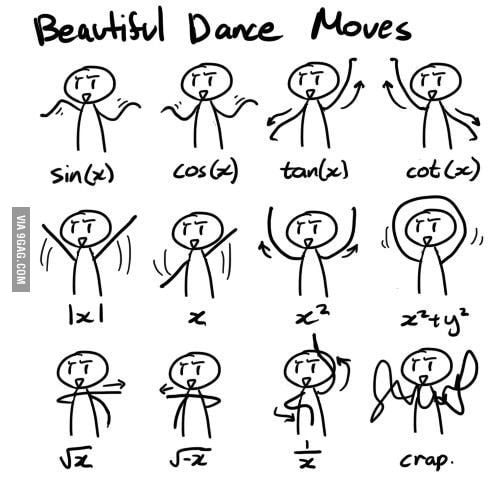

Where we see them most frequently is in any form of practice that operates at an intense pace. Athletes are a good case — especially any sport that operates in dyad or team competition such as fencing, martial arts, or soccer. This is always the case for martial practices, such as swordmanship in ancient Japan. Any samurai who stopped to think through his moves would be dead. You can also see this in swift-paced activities, ranging from surgery or stock trading to debating or legal argument.

In many cases, though, the truly competent are able to surface and examine their choices, describing and analyzing them through reflection and inquiry. In the reflective analysis, you will see why they are masters. You also see this level of mastery when a coach works with a learner — if you observe a master swordsman coach and younger swordsman, you will often hear comments that only grow from mastery … “You lost the match back there when placed your left foot at such an angle.”

You can also see it in the way that masters discuss and consider the art of their profession — there are two great scenes in which gunfighters describe their success. John Wayne as John Bernard Books in the Shootist teaches a youngster about shooting, to explain that it is not speed, but accuracy and the will to engage in combat that distinguishes the successful shootist.

In another memorable scene, Gene Hackman as Little Bill Daggett in Unforgiven tells a journalist much the same thing, explaining that accuracy and a cool head are the difference between his success as a gunman-turned-sheriff and those whom he has defeated. The journalist asks him, “What if they are faster on the draw than you are and still accurate?” “Well,” answers Little Bill, “then I guess I’d be dead.”

If you read The Book of Five Rings, you’ll see how Miyamato Musashi talks about martial arts. This is unconscious competence surfacing in reflection.

If I were to say it another way, one of the ways that the cycle works is that we learn the how and why of what we do as we move through conscious incompetence to conscious competence. It is the perpetual engagement with practice that brings us to mastery, freeing us to find the rhythm that is sometimes called “flow.” But to flow, we must be able to work at the unconscious level, focusing on everything other than ourselves. This is why our competence must be unconscious to constitute mastery.

Saying this, of course, I would be willing to substitute some term for unconscious that indicates an ability to bring to the conscious foreground the elements that we enact without thinking about them.

In another email he added the following thoughts

You might find it very interesting to read a book by Dave Lowry. The title is Autumn Lightning. Lowry describes his education in the martial arts, and talks about the Yagyu lineage of swordsmanship. If you find the story of the battle during the Osaka summer campaign when Munenori Yagyu single-handedly cut down seven warriors attacking the shogun, you’ll see what I mean. The fight was over before any of the shogun’s bodyguards even had time to react to the attack.

Lowry gives a marvelous account of the four stages, though he does not use the vocabulary.

In a sense, this is also what Malcolm Gladwell’s new book Outliers is about, and that’s the basis of the 10,000-hour rule.

Just a couple of quick thoughts (since doing justice to Ken’s words will take more time than I have at present).

The first thing I would like to point out is just how this email is classic Ken Friedman. Clear, lucid, thought-provoking, packed with knowledge and last but surely not the least, great examples. Where else can you find a Yagyu lineage of swordsmanship rubbing shoulders with John Wayne and Malcolm Gladwell! I know Ken virtually (having never met face to face) from his participation in the PhD Design listserv. Though his postings have reduced in number lately (becoming a Dean has something to do with it I think) they always have this extended erudite quality. I have to say that possibly the only reason I am on that list is to read his contributions. I have learned a lot from him over the years and it is great to engage in this conversation with him. BTW, he is a most interesting person, scholar, new-media artist, and design researcher, among lots of other things. Check out his wikipedia page to find out more. Truly a renaissance man born outside his time 🙂

Second, I am not really sure that Ken and I disagree here. I do not deny the importance of mastery and the need for it to be unconscious. The old joke about the millipede becoming unable to walk when they start thinking of their how they manage their feet, comes to mind. So automaticity requires processes to become unconscious. This automaticity happens in the actual doing of an activity – swordfighting or teaching. Neither can happen well if we are always second-guessing or reflecting on our choices. (Just a side note, the 10,000 hours that Gladwell talks about was noted in an earlier post by me here).

The only concern I have is that the use of the word unconscious may mislead us into thinking that mastery is just that and nothing more. Mastery to me requires an acute level of self-awareness. This reflection on action (or or Schon said reflection in action) is what I was trying to get at in my post, and if I read Ken correctly, at the end of the first email he essentially sympathizes with my view.

Note: This discussion or practice and automaticity reminds me of a great NYTimes piece on the foot movement of Roger Federer, the tennis player. The article starts as follows:

This is how Roger Federer transcends tennis before taking a single swing. He moves with feet that whisper when most squeak, guided by instincts more sixth sense than court sense, his head held still, as if balancing a book on top.

However, this doesn’t come easy. Federer’s trainer, Paganini,

designed drills specific to the tennis court… He made footwork fun for Federer again. Paganini also built three training blocks into Federer’s schedule each season during which the focus was on fitness and footwork instead of forehands.

. And when Federer is off his training it shows.

When Federer struggled in 2008, he had missed three of his usual training sessions in Dubai because of mononucleosis, the Beijing Olympics and a bad back.

[Read the entire article here and a lovely accompanying multimedia piece here.]

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks